United States

Luxury Law

This is the first edition of the Law Over Borders Luxury Law guide. The second edition is now available for viewing and purchase: Luxury Law

1 . Trademark

1.1. Sources of law

Although American copyright law has been a slow learner when called into the service of protecting the artistry of fashions, accessories and other fine goods across luxury categories (see below), trademark law has been supportive from the beginning, albeit from a purely commercial perspective.

Our trademark law evolved from the English model of granting exclusive rights to identifiers of sources of goods and, later, services; it therefore incorporates key principles from both English common law and equity. Unlike either copyright or patent protection, which the Constitution says can only be granted by Congress “for limited times,” under the use-based United States trademark system, as long as you can prove you are continuously using your mark in commerce among the states or from overseas into any state, your exclusive rights to that mark for your goods or services are theoretically perpetual.

Even though registration is not a prerequisite in the United States (either to the creation or enforcement of exclusive rights to a mark), except for those style and model marks that are anticipated to last only for a season or two, federal registration of core marks and even secondary marks is nearly always advisable. Filing through the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) under the broadly accepted Madrid System is practical and comparatively quick, but for complicated, multiclass applications for luxury goods or services, doing so is typically more trouble than it is worth. Using the WIPO method, an applicant can file one application for multiple nations at the organization’s headquarters near Lake Geneva. Filing through WIPO works brilliantly for so many participating nations—just not this one. As one examining attorney of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) once told me, “We are like children. We are very literal.” What she meant was that the office expects what, by international standards, are excruciatingly exact lists of goods and services in its applications—something that applicants filing through WIPO routinely fail to provide. To make your WIPO application acceptable to the USPTO, you will need to hire US counsel, but be mindful that, in nearly all cases of which we are aware, fixing the problem that way has proven more expensive than would have been the case had the applicant bypassed WIPO and instructed US counsel to file a national application directly with the USPTO in the first instance.

Given that the United States allows marks to remain unregistered and yet receive full protection under law, a simple examination of the USPTO database (TESS) will not suffice to give a reasonable measure of confidence that a proposed mark can be used without fear of a third-party claim. Consider that in light of the cost to a luxury brand if something goes so wrong that the product has to be pulled at launch (to name just one of several possible nightmare scenarios). That is the reason we strongly encourage our luxury clients, in other than limited and specific circumstances, to authorize us to conduct what is known as a full search of multiple databases.

Although response times vary widely due to workflow and other factors, an applicant can generally expect a turnaround time from the USPTO of between six to eighteen months, from application to registration, but that depends on how quickly an applicant responds to any office action issued by the examiner that would require a response in order to overcome a refusal to register.

1.2. Substantive law

For any non-functional visual element associated with a luxury brand—whether stylized designer initials on a gold bracelet or a hood ornament on a limousine—the key point to consider in determining if it can be claimed and registered as a trademark is if it identifies the brand as the source of the goods. That is why trademark law is sometimes called, without hint of cognitive dissonance, both a right of monopoly and a consumer protection mechanism. Consumers benefit because, if they see a familiar mark, they can trust that it came from the brand (or its licensee) they are seeking to patronize. And what business, caught on the competitive treadmill of a well-functioning market economy, does not secretly pine for the insouciant comfort of even a benign monopoly?

Trademark law in the United States offers a range of protection that demonstrably benefits brands in luxury categories, but the process only works when brand owners remain vigilant. Add to it the fact that luxury brands are particularly susceptible to counterfeiting and you can see why - in the USA, much of trademark law as applied to luxury goods and services is about having both a watchful eye and continued attention to detail. Although we all can name exceptions, the general rule is that luxury brands drive markets, not merely with standards of taste and quality, but by turning purchasing into an aspirational pursuit. With so much involved, and with so much at stake, trademark protection and enforcement should therefore remain an absolute priority for any luxury brand seeking to build and protect its reputation in the American marketplace.

1.3. Enforcement

Following a rough start in the nineteenth century, the core elements for federal trademark protection have remained remarkably consistent.

The mark must be used as a mark, not merely a decorative element. A design spread across the front of a T-shirt is not a mark for the USPTO - just a pattern on a shirt. However, the demure Lacoste crocodile or the Ralph Lauren polo player on the top left of the front of a knit shirt is a mark because it is consistently used that way to identify its source. Note that, in the luxury market, usages of that kind - indeed, of all the forms in which “logo” clothing and accessory products are made and sold - have helped expand our notion of where marks can be placed and what does and does not qualify as usage as a mark. Similarly, the marketplace for luxury automobiles is trained to spot devices used as marks on grillwork, at the rear and as hood ornaments; somewhere on the vehicle will likely be the model name - also a mark in most cases.

Moving off the item proper, hang tags that contain marks are excellent examples of usage of words and devices as marks. For anything portable, packaging is the next point on which items can be identified with marks. Indeed, for alcoholic beverages, bottle shapes (as trade dress) and labels (incorporating trademarks) are just about the only reliable ways to identify the source of origin of the contents, and in a market in which a bottle of red wine, for example, can cost a few dollars or thousands of dollars, the distinction (until the bottle is opened) is all about what is on the label. For either consumer goods or services, the use of a mark on a sales site to identify the source of what is being offered is also use as a mark.

Once granted, registrations must be renewed every ten years. Renewal requires demonstration to the satisfaction of the USPTO that the mark has been in continuous use in interstate commerce in the form substantially in which it was registered. Any goods or services no longer offered under the mark would need to be stricken from the registration at that time. Generally, other than for momentary gaps, the requirement is for continuous and (this is important) consistent use.

Another distinction of United States trademark law is the willingness of the USPTO and the courts to reject efforts to claim as marks those terms that, arguably, are merely descriptive of the goods and services they brand. Given the quantity of those marks that come into the USA from other nations, the USPTO has developed its Supplemental Register as a companion to its main trademark register, which is known as its Principal Register. A registration on the Supplemental Register provides modest but authentic advantages, and after five years, the opportunity arises to demonstrate secondary meaning. If the registrant can show that the registered mark has come to be known in the marketplace not as a mere description for the applicable goods and services but as a source identifier, the USPTO will permit the mark to be registered on the Principal Register if a new application is filed with sufficient proof.

Under precedent that developed in the past few decades, color can be a trademark in the United States. In the luxury area, the classic example is Tiffany, which has even taken the trouble to get its own Pantone shade for its distinctive robin-egg blue (Pantone 1837 Blue). Any jewelry maker with boxes that appear in shades sufficiently close will likely hear from counsel for Tiffany. Successfully claiming color as a mark on products themselves as opposed to their packaging is more challenging, requiring a clear showing of secondary meaning. Rather famously, Christian Louboutin was able to assert trademark rights in its red soles for shoes. Christian Louboutin S.A., et al. v. Yves Saint Laurent America, Inc., et al., 695 F.3d 206 (2nd Cir. 2012). Christian Louboutin lost the battle but won the war: the Second Circuit Court of Appeals held that Saint Laurent shoes that were red all over (soles and uppers) did not infringe on the registration held by Christian Louboutin for its red soles (giving the immediate win to Saint Laurent), but the Louboutin registration was held as valid and enforceable against shoes with uppers in any color other than red because Louboutin was able to sustain its claim that the soles had acquired secondary meaning.

2 . Copyright

2.1. Sources of law

The development of United States copyright law can be traced back to the British Statute of Anne (1710), through the United States Constitution (1789), to the first piece of federal copyright legislation, the Copyright Act of 1790. One of the singular features of the common law method of jurisprudence is that, during key moments when judges have not had available to them the statutory tools to provide what they felt were just solutions, they have reorganized whatever was available to approximate the results they believed to be fair. That is essentially the origin behind the evolution of the current Copyright Act of 1976 into an instrument for protecting fashions and other categories of industrial design that inhabit the luxury market.

2.2. Substantive law

Clothing, accessories, aircraft tailfins and all the rest of it are nowhere directly mentioned in the statute, and protecting designs of those items was never seen as a purpose of copyright law until comparatively recently; but now it is, at least to a point.

The courts have thereby filled a statutory gap in that the United States has never adopted EU-style legislation to protect many of the designs, both classic and au courant, of the kind familiar to the international market for luxury goods. It is therefore understandable that, in 1980, when Kieselstein-Cord v. Accessories by Pearl, Inc., the first case of consequence protecting a luxury fashion design was won (by this law firm), the appellate court began with, “This case is on a razor’s edge of copyright law.” (632 F.2d 989 (2d. Cir. 1980)). That case affirmed copyright protection in ornamental elements of the buckles on two styles of luxury belts. The decision relied heavily on the doctrine of conceptual separability: if you can conceptualize the copyright-protectable decorative elements of the item as separable from its utilitarian elements (the functional parts of a belt buckle, for instance), the decorative elements are protectable if they meet minimal standards of originality.

The Supreme Court brought order to a developed body of law under which various federal appellate courts had applied different standards in examining whether a particular decorative element in fashion items was protectable by copyright. In Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 137 S. Ct. 1002 (2017), the court effectively said that, if you could conceptually take a fabric design off a garment and frame it as art, it could be protected by copyright if it met minimum standards of originality. For three-dimensional elements, such as the belt buckle decorations of the Kieselstein-Cord case, the test would be whether they could, again conceptually, be put on pedestals as sculpture if they could pass the same minimal standards of originality. That is, the ornamentation on a belt buckle or bracelet clasp might be protectable, but only to the extent that it has nothing to do with keeping the belt or bracelet closed.

That still leaves garment shapes—the core of what is typically considered clothing design—unprotected in any way, a fact that helps explain why companies like Zara have such free reign in the USA to copy luxury designs. There have been several attempts in Congress to provide some legislative protection for clothing designs, albeit for shorter periods of time than for allowed works protectable under the Copyright Act in its current form. All of those efforts have failed.

Whenever it is asked (as it has been for generations) why the Copyright Act does not recognize droit moral (the inalienable moral right of the creator not to see his or her creation altered or disturbed by others) in the protection of works of art or literature, it is in part because assessing artistic or cultural worth is not seen to be the business of the legislature or courts. Your copyright is your property—not an extension of your personality or your personal rights—and that is where any legal inquiry into what you can do with it will both start and end.

There are two areas of US copyright law that often remain in equal parts mysterious and frustrating to practitioners from other countries: the concepts of work-made-for-hire and fair use (in its American iteration). Both are statutory and stem in different ways from the core US conception of copyright as a property right and not a personal right: a work protected by copyright is legally a commodity, as fungible in the marketplace as lumber or automobiles.

It is therefore possible for an author fully to divest himself or herself of all rights to his or her creation, from the start, as a work-made-for-hire, such as when making contributions to collaborative works or whenever doing anything creative and protectable in the service of an employer. The former was added to the law in good measure to protect the owners of motion pictures, and the latter was provided to assure that businesses can confidently use the work product provided by employees without restriction (in the absence of contractual provisions stating otherwise). Due to the work-made-for-hire concept, a frustrated CGI artist cannot demand that a film be pulled from distribution due to an unresolved creative dispute, and the employee who designed a fabric pattern cannot make a similar claim about a dress with that pattern that found its way into the retail channel over his objections.

Although what is protectable by copyright in the area of fashion design therefore remains limited, what protection can be had lasts for the same long term of copyright as it applies to a novel or film: the life of the author plus seventy years. For works-made-for-hire, the term is ninety-five years.)

2.3. Enforcement

If a work is a statutorily defined “United States work,” registration of the copyright in the work with the federal Copyright Office is a prerequisite for commencing an action for infringement (17 U.S.C. §101). There are historical reasons for this largely anomalous (by world standards) insistence by the USA that copyrights must be registered, but that requirement has been enforced so strictly that mistakes made in applications that mature into registrations can, in certain cases, cause the registrations to be held invalid and whatever litigation that had been commenced to enforce those registrations to be dismissed. Add to that the cumbersome and often confusing online application process, and it would be hard to fault anyone who did not have to register a copyright in the USA (that is, anyone from outside the USA) to consider skipping the registration process entirely.

We continue to counsel in most cases not to do so, however. Among other benefits, the registration certificate brings with it a presumption of the validity of the copyright; if the claimed infringer believes otherwise, it is its burden to prove that. Just as important, online retailers and others in US commerce are used to the comfort of seeing a valid registration as an imprimatur for protectability, and having a registration certificate to attach to a cease and desist letter or takedown notice is typically a good way to bring potentially decisive firepower to bear.

Fair use started as a judge-made concept, but it has been codified in the current Copyright Act (17 U.S.C. §107). In simple terms, the statute lays out four factors—strictly advisory as enacted but unfailingly applied by federal courts as if they were legislated requirements—to assess whether a copyright-protected work may be used in some form, format or manner by others without permission. Although the provision’s terms are simple, clear and flexible, American copyright lawyers make a parlor game of trying to predict how pending fair use cases will come out. That is because, as applied by the courts, the fair use doctrine can sometimes appear to slam through copyright law like an errant football. For instance: ever since Andy Warhol began creating silkscreens of real people and things (he started in 1962, with the US one-dollar bill as his subject), his practice of basing them on images (largely photographs) made by others had been accepted as fair use. Suddenly, nearly sixty years later, that was no longer necessarily true (Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith,992 F.3d 99, (2d Cir. 2021), amended by (No. 19-2420-cv), 2021 WL 3742835 (2d Cir. Aug. 24, 2021)).

For the makers and vendors of luxury goods (and that certainly includes works by famous artists), therefore, to resolve the question of whether what you are doing considered fair use, the sensible course of action is to consult with US copyright counsel; in doing so, be mindful that the ongoing unpredictability of judicial interpretations of the doctrine will continue to challenge even seasoned practitioners.

3 . Design

3.1. Sources of law

Design patent law had, for a long time, an identity crisis. It was drawn up in the nineteenth century to provide protection for ornamental designs in useful articles—in particular ornamental designs in cast iron, but also creative designs of fabrics, rugs and clothing of the era. At the time, there was no means of protecting the ornamental designs because copyright law did not extend to three-dimensional works, and patent protection was only available for the functional and utilitarian aspects of articles of manufacture. Efforts to remedy that deficiency ultimately came to fruition in 1842 in the form of the first design patent law (Act of Aug. 29, 1842, ch. 263, sec. 3, 5 Stat. 543, 543-44). That statue was the foundation for modern United States design patent legislation, through the current law, which provides protection for “original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture...” (35 U.S.C. §171).

3.2. Substantive law

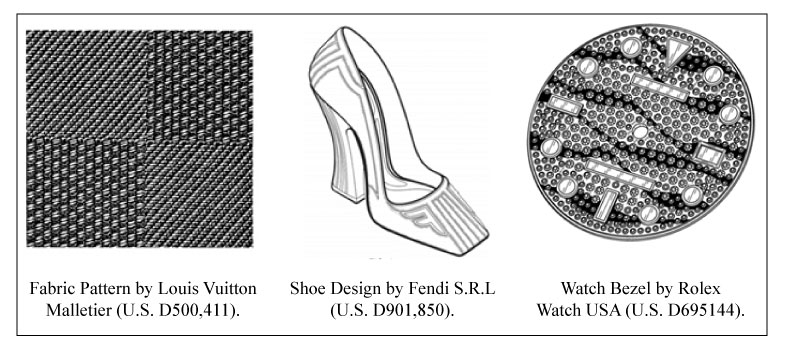

Today, all manner of ornamental design in luxury articles can be protected under design patent law, including fabric designs and patterns, articles of clothing, and consumer products, as shown in the examples below:

The design must contain novel and non-obvious ornamental features that are not purely functional. The invention must be new and non-obvious. Unlike copyright and trademark law, the inventor’s own prior public disclosure and use of the subject design may create a bar to obtaining a design patent. The law does, however, give a one-year grace period during which the inventor may publicly disclose and use the invention without creating a bar to patentability.

In contrast to the procedure in many other countries, a design patent application in the United States must be filed in the name of the inventor. The application can, however, immediately be assigned to an entity. The employer of an inventor whose design was created for the company should have an employment agreement in place that requires employees to make such an assignment and to cooperate in the prosecution of applications. The USPTO typically takes twelve to eighteen months to grant a patent based on an application. A granted patent lasts for fifteen years.

3.3. Enforcement

After issuance, a design patent can be enforced against any person or entity that is infringing the patented ornamental design. Determining whether there is infringement is a two-part test:

- the court must first construe the claim to determine its meanings and scope; and

- the fact finder (that is, the judge or the jury, as the case may be) must compare the properly construed claim to the accused design.

During claim construction, design patents “typically are claimed as shown in the drawings” contained in the registration, but construction can be helpful to “distinguish[] between those features of the claimed design that are ornamental and those that are purely functional,” because the functional elements of a design cannot be part of the claimed subject matter (Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa Inc., 543 F.3d 665, 679-80 (Fed. Cir. 2008)). In comparing the claim to the accused design, the “ordinary observer” test is applied, with the fact finder seeking to make the comparison through the eyes of an observer familiar with the prior art, “giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, two designs are substantially the same, if the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer, inducing . . . purchase [of] one supposing it to be the other, the first one patented is infringed by the other.” (Id. at 670, 677.)

An action for design patent infringement typically seeks two remedies:

- an injunction against further sales of the infringing product; and

- damages to compensate the patent owner for the infringement.

A unique feature of the law that has brought more interest to design patents in recent years is that it provides an alternative measure of damages not available for utility patents. Specifically, 35 U.S.C. § 289 states that whoever “sells or exposes for sale any article of manufacture to which such design or colorable imitation has been applied shall be liable to the owner to the extent of his total profit.” A recovery in the event of a previously profitable infringement of the design of a luxury item could therefore be potentially significant—if collectable.

4 . Right of privacy, publicity and personal endorsement

4.1. Sources of law

Unlike copyright, trademark and design patent law, privacy and publicity are governed largely by state law. Currently, over thirty states recognize the right of publicity in some form, either under a state statute, state common law or both.

4.2. Substantive law

Although the privacy side of these twin rights can be said to apply equally to all, the right of publicity is, at its core, largely a benefit to those persons, such as celebrities, who can monetize their personalities. The classic rule was that the right expires on the death of the rights holder, but a majority of the states that recognize the right for their residents now extend it past death. The term and other considerations vary from state to state, with California, the home to many celebrities, recognizing the right for seventy years after death. Two other states (Oklahoma and Indiana) take it to a full century of protection. New York State is a newcomer to the concept, courtesy of legislation enacted in 2020 that grants post-mortem publicity rights for forty years following death.

Although some states will infer a license of publicity rights from a course of conduct, good practice, as with nearly all important business relationships under the common law, is to have a properly detailed agreement. See Madrigal Audio Laboratories, Inc. v. Cello, Ltd., 799 F.2d 814, 822, 230 U.S.P.Q. 764 (2d Cir. 1986). As with any license, one covering the right to use a celebrity’s name, image, voice and other indicia of personality requires a clear grant of rights, performance and payment provisions, but of particular sensitivity these days is the morals clause (also called a moral turpitude clause), which grants the licensee the right to exit the deal, along with other rights, if the celebrity participates in wrongful acts during the contract term.

It has long been the practice, whenever engaging a celebrity, influencer or anyone else to work with a luxury brand, to add a morals clause. It gives a contractual “out” in the event that the person gets into serious trouble, such as criminal activity or the commission of an act that is immoral under generally accepted standards (the definition of which could vary greatly depending on era and circumstances). In the current environment in the United States, where the #MeToo movement has risen to have such a powerful public presence, and where the recently or habitually famous can be “cancelled” (the electronic-age equivalent of “shunning”), for making statements that are potentially dangerous to a brand—even if thoughtfully expressed or factually correct - luxury brands typically insist on morals clauses that give them broad leeway. It is therefore not unreasonable for a brand to seek to include a clause that gives it the right to push the “eject” button immediately and without notice for any reason it deems appropriate for preserving its reputation.

The celebrity may insist on exit compensation, whether determined later by arbitration or otherwise, but that can be the subject of negotiation. The main point is that, if the celebrity becomes a potential liability, even under circumstances that, in a more gracious age might have seemed unfair or even unjust, a luxury brand can easily find itself in an incredibly difficult position overnight, and contracts should be drafted with that in mind.

4.3. Enforcement

Celebrities, in the popular definition of people who are well-known for being well-known, can bring great benefits as licensors and endorsers, as many luxury brands have demonstrated over the years. Running in a parallel course now are influencers who, even if self-made, self-taught and free from supervision or editorial oversight, can yet have a powerful effect on brand recognition and acceptance.

Conclusion

An age of interlayered surprises breeds unexpected actions and counteractions. In response, custom and the law may bend, the former in curious ways and the latter in a manner intended to catch up. This is, accordingly, a good moment for luxury brands to pause, reassess their values and priorities and to check in with counsel. Chances are, something different will need to be done to keep legal practices both creative and vital.

5 . Product placement

Product placement has become routine in films, video games and other media. Although that ubiquity may make audiences and consumers comfortable with having de facto advertising embedded in content, because US branding contracts of all kinds must be exact to be enforceable, the rule remains that great care needs to be shown in the drafting phase of placement agreements. That is largely because, unlike traditional advertising, in which the brand controls the totality of the message, product placement, by definition, means that the brand appears in a subordinate role to a larger message controlled by others. Luxury brands must, therefore, be demandingly exact in the description in product placement contracts as to:

- what product will be featured;

- in what context in the story or sequence of events it will be shown;

- how long it will appear on screen or, for interactive content, the average amount of time it likely will appear;

- how it will be used, adapted or otherwise incorporated into the action or, for interactive content, the user experience;

- with what other products will it be shown or to which it will be compared in some way; and,

- notably for luxury goods, how will the overall effect remain consistent with the brand’s message of product exclusivity and desirability?

Of particular sensitivity, of course, depending on product and brand, are uses in connection with alcohol, tobacco and sex and violence of any kind. All of that needs to be mapped out in detail. For example, if the hero wears your watch, you might want to specify that he checks it, in a close-up of the dial, as seconds tick down as he works on defusing the bomb, but you might choose not participate in that sequence if, after so doing, the bomb blows up in his face. Please note the adage that all digital content is presumptively permanent: whatever goes in has the potential to linger for years afterward in both its original form and YouTube videos and other pickups made by others.

6 . Protection of corporate image and reputation

The United States is a major consumer of luxury goods from around the world but, it is not a major producer in key categories. When it comes to the question of image and reputation, key players are typically based outside the USA. Even domestic brands source much of their manufacturing overseas. All of that contributes to making questions of importation of particular consequence for the American market, an importance that inevitably raises the issue of gray market goods (or parallel imports as they are sometimes—and more neutrally—called).

Gray marketing has long stood on the wobbling cusp that separates the American zealousness in protecting proprietary rights from the American ethos of value shopping (that is, to get what you need or desire as cheaply as circumstances might allow). The "cheat" about gray marketing is that the consumer gets pretty much what he or she wants from a luxury (or other) import even as the authorized American distributor or vendor is bypassed. That business model works generally as in most other countries: a maker of a high-end camera, for example, sells the same camera around the world, but it sells into the US market only through the authorized importer and distributor—which may be an affiliate of the brand owner. The authorized importer may offer a warranty customized for the US market. It is sometimes the case that the authorized version of the camera and a version coming into USA in a gray or "parallel" manner would also have functional or aesthetic differences from the version sold into the USA through the authorized distributor. The brand owner might also sell the camera in the USA under a different trademark, in the hope of further diminishing the attractiveness of the gray product.

Under any scenario, gray-market importing is only worthwhile for third-party importers or distributors if the price to the consumer of the version sold by the authorized participant is greater than that charged by the parallel importer or distributor. Due to a global market, the transparency brought on by online connectivity and the vicissitudes of the distribution channel, prices and discounts can fluctuate dramatically for some goods, making gray-market importing a potentially riskier business than it was in the last century. A further complication is that, as the economy has globalized, consumers can now easily order gray-market goods, whether knowingly or not, through online sources such as eBay.

Generally, gray marketing is not illegal in the USA, in fair measure due to the "first-sale doctrine." That is, if something is sold by the trademark owner into commercial channels, its resale in the USA is not something that the owner of the mark can seek to control—even if the first sale was outside the USA. Where things get potentially difficult (which, in the USA, means they can potentially trigger complex litigation) is when there are material differences between the authorized goods and the gray goods such that marketplace confusion might arise. It is worth noting that the United States International Trade Commission (ITC) will sometimes come to the aid of trademark owners in enforcing their right to block the importation of gray-market goods that are materially different from the goods bearing their marks that are authorized for sale within the USA.

The law has remedies for wrongs, but at the end of the day, but there is no remedy for a practice legally done, of course. About the easiest way to avoid problems with gray-market luxury goods is to price products uniformly, as much as possible, throughout the markets into which they are sold, worldwide. Another tool is to make it known, in advertising and through the media, what benefits would be had from buying the authorized version of a given product for the USA (such as, for example, receiving a longer warranty period or having servicing performed promptly and within the USA). The United States remains committed to enforcing intellectual property rights, but just about everyone loves a bargain, even in the luxury market, and that basic fact should always be considered in making the calculations on what to import into the USA and at what price relative to prices offered in other countries.

3-6 PQE Corporate M&A Associate

Job location: London

Projects/Energy Associate

Job location: London

3 PQE Banking and Finance Associate, Jersey

Job location: Jersey

Alan Behr

Alan Behr Tod Melgar

Tod Melgar