Sign up for our free daily newsletter

YOUR PRIVACY - PLEASE READ CAREFULLY DATA PROTECTION STATEMENT

Below we explain how we will communicate with you. We set out how we use your data in our Privacy Policy.

Global City Media, and its associated brands will use the lawful basis of legitimate interests to use

the

contact details you have supplied to contact you regarding our publications, events, training,

reader

research, and other relevant information. We will always give you the option to opt out of our

marketing.

By clicking submit, you confirm that you understand and accept the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy

I was interested to see the following headline: “Robo judges could make legal rulings, says Master of the Rolls”, jumping out at me from the online publication, Legal Cheek. I was drawn in to read more, but not surprised to see this headline, nor to read the possibility of legal decisions ordinarily undertaken by trained judges could be undertaken by artificial intelligence (AI) in the future.

Anyone who knows the Master of the Rolls Geoffrey Vos, or who has heard him speak, wouldn’t be too surprised by this overture; he has previously spoken enthusiastically of an integrated online civil justice system and the use of technology to allow “legal rights to be cheaply and quickly vindicated.”

He also cautioned that the coming generation, “will not accept a slow paper-based and court-house centric justice system… that the use of technology by the courts is not optional, but inevitable and essential.”

We read almost daily about the potential of AI, from its influence and impact on society and how businesses operate, to the power of generative AI to transform the legal industry by automating and enhancing various aspects of legal work, such as contract analysis, due diligence, litigation processes and regulatory compliance. Indeed, it has not gone unnoticed with some law firms leading the way by developing and leveraging AI as part of their daily operating model to assist with research, disclosure and to assess risk exposure.

There is no doubt that technology is redefining the legal field and society. As practitioners we have to equip and prepare ourselves for the changing landscape and the way we work with and keep pace with technology, otherwise we will get left behind and even become redundant due to our failure to keep pace with this pervasive technology we call AI.

Online justice

Additionally, there is a push for online justice as the government seeks to transform our justice system. However, online justice is not without its concerns around access to justice, due process and the ability of vulnerable individuals and those who are digitally excluded to interact with the legal system in this way (for instance, being subjected to decisions made by AI).

Of course, the Master of the Rolls makes it clear that there would be an option to appeal a decision made by a robot to a human. I am assuming the human would not be able to consult ChatGPT to assist with the appeal… but with all seriousness, it is true that the potential of generative AI to be trained with the requisite knowledge could and will make judicial decisions far more quickly than a human, being able to take seconds rather than weeks for the heavier laden of cases.

If you are in any doubt, search for an item on Google, any item. I took the opportunity to search for myself – I. Stephanie Boyce – and within about 0.40 seconds, 3,230,000 results were found. Of course, they were not all in relation to yours truly, resulting in different permeations of I. Stephanie Boyce, but you get the picture as to how fast AI is – far quicker than asking any human being to produce this information within this time frame, virtually impossible for a human being to do so.

Will this be the case for judicial decisions? Well, why not – why wait weeks or months when you can get a judicial decision in seconds? And why stop there? AI could also be used to replace jurors and provide sentencing decisions, freeing up time and resources. But we are a long way from this – years away, many years away, I hope.

Lack of oversight

The UK government published its AI white paper recently, which has now closed for consultation. The white paper states the UK government would prefer not to legislate, saying it “will avoid heavy-handed legislation which could stifle innovation and take an adaptable approach to regulating AI.”

The government has indicated it will do this by empowering existing regulators to prepare tailored, context-specific approaches that suit how AI is used in each specific sector. This approach I find somewhat bizarre and risks unintentional exclusion and higher error rates to go unchallenged. Since the white paper was published, we have seen numerous individuals including CEOs, godfathers of tech and ex-Law Society presidents (namely me), that have come out very forcefully to say the UK government needs to take a different approach than that set out in the white paper and instead needs to lead and show leadership. The government has since changed its position slightly from that set out in the white paper.

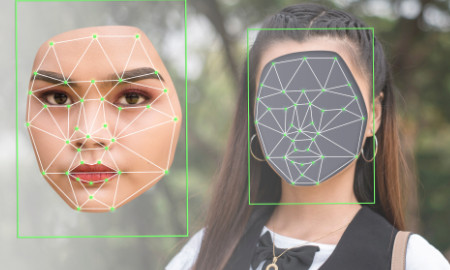

Most of our current laws were not written with AI in mind, creating real life issues to go unaddressed. We now have technological systems that can converse with us as if they were other people, with the ability of ChatGPT to recreate the most human of traits. And while there are plenty of laws that regulate how we behave as humans, there are little or no laws that govern AI. While I appreciate the need to not hamper innovation or growth, leaving it to regulators alone to solely rein in AI may do more harm than good, leaving damaging but legal AI in place with no effective framework for the enforcement of legal rights and duties. Clearly our European colleagues in the European Parliament think differently as they have set out a legal framework on AI with the Artificial Intelligence Act seeking to ensure safety and fundamental rights, with a number of restrictions in place around ChatGPT and predictive policing.

Effective regulation requires the full weight of government. While regulators can influence behaviour through education, training and the setting of standards, government legislating in this space can address bias and discrimination before they arise by ensuring AI technology is developed responsibly, safely and transparently. They also need to ensure that there is accountability, which will positively impact global perceptions of AI as well as boost its legitimacy and prominence across all business sectors and jurisdictions, and in turn, the trust and confidence of those who use it and are subject to it.

Regulation and compliance typically fall behind the adoption of new technology, playing catch up for the most part. The AI community wants regulation too: imploring governments to regulate AI to set mandatory, enforceable requirements and standards to prevent rogue operators and protect the integrity of the responsible, while mitigating any risks to human beings. Most of us want to see AI being used for the good of all humanity; we don’t want to see one outlier ruin the integrity of AI and the whole industry tarred with the brush of unorthodox actors.

Guiding principles

As president of the Law Society of England and Wales in March 2021, to aid the governance of digital legal services we launched a set of ethics principles to guide the development and use of lawtech, urging for greater accountability and regulation in this space. The principles were the culmination of two years of work, including consultations with law firms, developers and regulators. The principles are:

Compliance: Lawtech should be underpinned by regulatory compliance. The design, development and use of lawtech must comply with all applicable regulations.

Lawfulness: Lawtech should be underpinned by the rule of law. Design, development and use of lawtech should comply with all applicable laws.

Capability: Lawtech producers and operators understand the functionality, benefit, limitations and risks of legal technology products used in the course of their work.

Transparency: Information on how a lawtech solution has been designed, developed, deployed and used should be accessible for the lawtech operator and for its client.

Accountability: Lawtech should have an appropriate level of oversight when used to deliver or provide legal services.

The aim of the principles is to empower the solicitor profession to understand the main considerations they should make when designing, developing or deploying lawtech. It also aims to encourage greater dialogue between the profession and lawtech providers in the development of future products and services, helping solicitors to unlock the benefits brought by digital transformation by providing a starting point to assess the compatibility of lawtech products and services against professional duties. Likewise, it also aims to help lawtech providers understand the regulatory parameters of solicitors’ practice, embed trust and build market-ready solutions.

The five main principles should inform lawtech design, development and deployment. They also recommended that the five principles were linked to an overarching client care principle, to reflect the use of lawtech in a way which is compatible with solicitors’ professional duties to their clients.

Government approach

The government recently published five principles of its own: safety, security and robustness; transparency and explainability; fairness; accountability and governance; and contestability and redress, taking an adaptable approach to regulating AI. I am concerned by the lack of oversight and laws and what this might mean for individuals, for businesses and our society in this fast-moving space.

We have since heard the prime minister go further than set out by his government’s own white paper, talking about the need to impose guardrails and acknowledging that AI could pose an “existential” threat to humanity, indicating that the UK should lead the way and write a new set of guidelines to govern the industry. With the consultation period for the white paper now closed it remains to be seen as to who will write these new guidelines. What I do know is that it will require a collaborative, cohesive approach from all regulators and not just in this country but globally.

What needs to happen is a global response to a global problem, all companies who develop and use this technology need to be held to account for the technology that is being developed and to stem any harm that may flow from these technological tools before they are released. Regulation would also undoubtedly result in huge benefits for gaining and maintaining the trust and confidence of the public.

With the use of AI on the march, the public must be assured that its increased use poses little threat to the existence of humankind, and where it does, that there are appropriate guardrails in place to prevent serious harm and eradicate any underlying biases and unfairness that may exist. So just because there may come a time where AI can make judicial decisions, it doesn’t mean it should. My advice is to proceed with caution and care, so as to manage the benefits and risks of AI accordingly.

I. Stephanie Boyce is the immediate past president of the Law Society of England and Wales. In March 2021 she became the 177th, the sixth female, the first black and first person of colour to become president.

Email your news and story ideas to: [email protected]